…and my life is still, trying to get up that great big hill, of hope, for a destination. I realized quickly when I knew I should, that the world was made up of this brotherhood, of man…And so I wake in the morning and I step outside, and I take a deep breath and I get real high, and I scream at the top of my lungs, “What’s going on?” –Linda Perry, 4 Non Blondes, song “What’s Up?”, 1993

Recently, I made an overnight trip to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to visit my “artist buddy” Jane Filer. Several years ago, I wrote a biographical story about her life and her paintings after we met in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Read: Being Jane Filer Two of her pieces are in our living room, “Eclipse” and “Elephant Journey”, both of them highlighted in the article.

The premise of traveling to her home was a painting I noticed and kept returning to on her website janefiler.com under “Available Work”. It was entitled “Above the Bridge”. I finally called Jane and said I was really drawn to this one but needed to see the painting in person to know how it made me feel. She agreed, and we set a date.

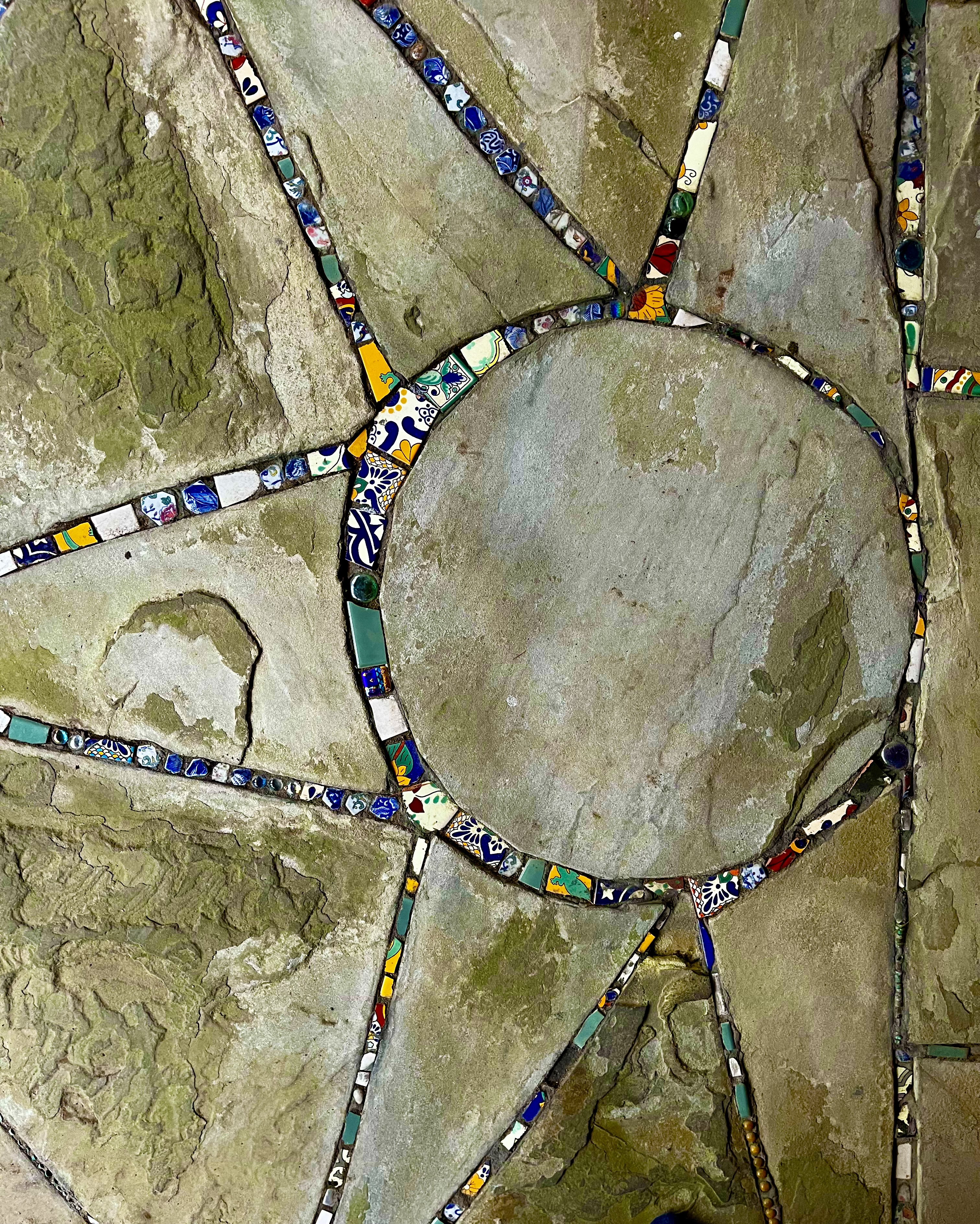

It was two years since we had last seen each other, but we fell into conversation easily, as friends generally do. I noticed the changes in her home and property since the last time I was there. A large shed had been renovated and turned into a gallery for on-site weekend art shows, there were now two cats in residence, and she started an outdoor project of reconfiguring stone pavers by outlining them with colorful pottery and pieces of glass. I picked up an alabaster egg on a windowsill to admire its smooth shape and beautiful translucency in my hand. She insisted that I take it home.

When we went into the studio to view the painting, Jane showed me a recently finished piece entitled “Congregation”. It was colorful and typical of her “primal modern” style which emanates from her dreaming-while-awake imagination. Then she moved “Above the Bridge” to the easel for my viewing. And I just knew. This was going to be my painting.

The question is why? What resonated? Like so much of Jane’s art, there are layers upon layers to see and feel and think about. Then you bring your own meaning to it. The details I first noticed were two small black figures “under the bridge”. One is swimming strongly onward; the other is rising to the surface with one arm extended straight upward.

Musing about these small figures under the bridge with the larger world painted above the bridge struck me as symbolic and meaningful. Right now. These are actions to aim for; onward and upward. For anyone, for everyone.

In the current American climate, where everything is moving in the direction of political dismantling and destruction, many people want, and need, to find what can be done now, while also moving toward the future. Then I thought; these are the same movements–the actions we take in the present are what we will continue to do in the future.

Poets, artists, and writers are often sources of inspiration about what is needed in trying times. Art cuts deep to the marrow of reminding us how to refocus and get moving in stressful times, whether personal, cultural, political, or global.

Almost every generation of Americans for the past 250 years has encountered and eventually survived some kind of catastrophic period; revolution followed by war, destructive civil war, two world wars, years of severe economic depression, McCarthyism, a decade of political assassinations and riots, the unpopular 10-year Vietnamese war, murderous terrorist attacks, devastating viral pandemics. Just as it seems that so much changes within generations; history teaches that great things can, and do, persist after turmoil.

We all have a part in shifting the story. –Joy Harjo, 23rd U.S. Poet Laureate

Inside the head spinning turn of extreme change our democracy is currently undergoing, what part, as Harjo suggests, can we play in shifting the story?

It’s really the same part we play throughout life. First, we learn, we adapt, and we move forward with what we can control. Adaptive change often means taking on complex challenges that seem impossible in the beginning. Staying immobilized doesn’t help the situation. You have to try. Like the feeling a piece of art instills, we bring the meaning and sense to what can change and what we can change.

I read a story about a woman, Maureen Morris, who opened a coffee shop called Back Street Brews in a small, politically polarized Virginia town several years ago. During a time of stridently vocal opposing sides, she pushed the notion of a gentler America inside her café. Everyone was welcome to openly discuss their views, but there would be no attacking or judging. “If it comes up, as long as it’s respectful, you can talk about whatever your beliefs are…If you are a staunch this or staunch that, I always say, keep that out of here.”

Customers began asking about each other’s family or simply shooting the breeze over coffee. Discussion groups of varying topics began showing up. Maureen’s café became known as a quiet force of civility while crossing the political divide inside a public space. Neighborly ways, respect, and social ties persist.

Ordinary people created a community where they listen and speak to each other without shouting. All due to one woman’s insistence that, amid the divisiveness of an era, she would lead from the strength of her beliefs. “It’s affecting people. Not me. Not in my bubble. We’re going to be fine, everyone! We’re going to land on our feet in my coffee bubble.”

This is how an individual shifts the story. By accomplishing small things that perhaps no one notices in the big picture but has real impact on people’s lives. Everyday lives. We nurture and nourish everyone in our circle of family, acquaintances, friends. We take care of ourselves. We stay true to our values.

Because there is a remnant of change that begins with one act of kindness, one spoken truth, one considerate conversation, one shared laugh, one poem, painting, or story. These are ways to move the narrative.

A brief scene in the old Hollywood movie, Casablanca, with Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman offers another example of one person’s action to restore balance.

During a busy evening in Rick’s American Café, a casino and piano bar in Casablanca, there is a scuffle when the thief Ugarte is discovered by authorities. After Rick refuses to hide him, Ugarte is hustled out in a loud commotion surrounded by police. The music stops and customers sit mutely, in stunned silence.

Afterward, Rick (Bogart) apologizes for the uproar, reassures everyone that the trouble is over, everything is all right, and they should continue having a good time. He speaks calmly to the crowd, tells Sam to resume playing, and without breaking stride re-rights an overturned wine glass on a table.

…the saloonkeeper’s cool response to Ugarte’s arrest and his instruction for the band to play on could suggest a certain indifference to the fates of men. But in setting upright that cocktail glass in the aftermath of the commotion, didn’t he also exhibit an essential faith that by the smallest of one’s actions, one can restore some sense of order to the world? –Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow

As we find our part in “restoring some sense of order”, we also climb “that great big hill of hope”. And make it a destination.

Poems and songs are written to get our minds thinking…in an unexpected way.

TROUGH

There is a trough in waves,

a low spot

where horizon disappears

and only sky

and water are our company.

And there we lose our way

unless

we rest, knowing the wave will bring us

to its crest again.

There we may drown

if we let fear

hold us with in its grip and shake us

side to side,

and leave us flailing, torn, disoriented.

But if we rest there

in the trough,

in silence,

being with

the low part of the wave,

keeping our energy and

noticing the shape of things,

the flow,

then time alone

will bring us to another

place

where we can see

horizon, see the land again,

regain our sense

of where

we are,

and where we need to swim.

–Judy Brown

...Come dance with the west wind and touch on the mountaintops

Sail o'er the canyons and up to the stars

And reach for the heavens and hope for the future

And all that we can be and not what we are...

–John Denver, song The Eagle and the Hawk, 1971

Fun Final Photo Shoot: