On a warm October weekend in 2024, I lived in a bedroom on the lower level of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Shining Brow” home outside the town of Spring Green, Wisconsin. He designed and built it more than 100 years ago in the rolling farm and woodlands where his Welsh ancestors had settled as farmers in the 1840’s. Taliesin, which means Shining Brow, is the Welsh word by which the 800-acre estate is known because it sits on top of the hill and blends seamlessly into the landscape around it. I wanted to experience Wright’s unique design philosophy by spending time in this geography.

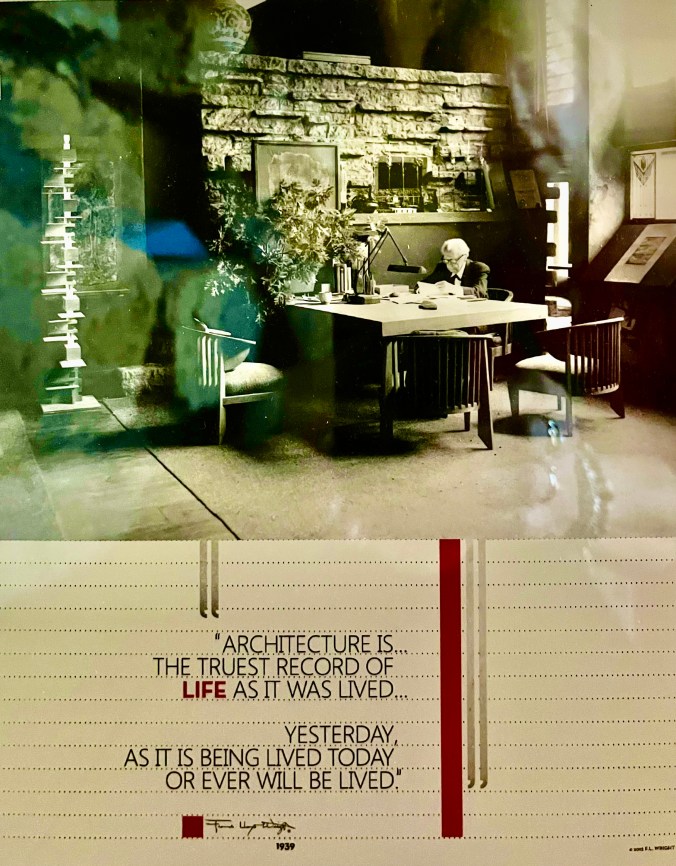

Frank Lloyd Wright [1867-1959] was an American architect of renown in the last century. He designed houses and buildings in careful harmony with the natural environment, using the landscape’s resources, materials, and topography as guidelines. In his houses everything complements nature; low slung, wide, cantilevered eaves and flat rooflines, walls of windows framed in wood, and always a large, centrally located open fireplace. He designed the lighting and the furniture too, believing that spaces [both practical and aesthetic) should serve how people move and feel within them.

Since I was a young child, I have been intrigued by houses, how we create spaces in them that resonate with our spirit. I remember when I fell in fascination with Frank Lloyd Wright as a creator of special “places”. In my first job as a Pediatric nurse in Madison, Wisconsin, one of my colleagues lived with her boyfriend and several other people in a house they were renting. When I walked in, I felt something visceral; this was a place and a space that made me feel like I wanted to wake up there every day. A huge open fireplace in a large living room, red polished floors, floor to ceiling walls of windows bringing light and outside greenery in. I asked my friend if another bedroom was available to rent. I would have moved in that day.

Frank Lloyd Wright was a complicated genius, as many artists are apt to be. As the only son in an extremely dysfunctional marriage between a preacher and a teacher, his mother put all her efforts toward the goal that Frank would be an architect. He played for hours as a young boy building complex designs with geometric shaped blocks, called Froebel’s Gifts and Occupations, which she ordered from Germany. The “Gifts”, used educationally in advanced German kindergartens, consisted of different sized blocks, pegs, pieces of colorful paper or yarn. They were instrumental in fueling his imagination for crystalline and geometric design shapes.

The premise of living at Taliesin for a weekend was a workshop on bread baking taught by Bazile (Elizabeth) Booth, a Spring Green baker. It was offered to a small group. Only ten people. Because we were paying guests and living on the grounds, we had the privilege of a private tour of the house and the Hillside School. The school, designed by Wright, was his first professional project in 1886. It was built for his aunts who taught a progressive day school curriculum. A later wing was added as an architectural drafting studio for interns, fellows and apprentices who lived and worked on site. We had freedom to wander the estate during the weekend, so I took advantage of photographing everything Wright designed–the school and apprentice studio, the big red barn, the Romeo and Juliet windmill, the family Unity Chapel, as well as the house and grounds.

Frank inherited his father’s short stature and good looks, his charismatic charm and engaging ability to tell a story, his lifelong talent and love for music. Wright was a poor student and never obtained a degree in his chosen field. He had a terrible reputation with finances, cost overruns, and not meeting timelines. He presented himself with panache and flair in both speech and attire. Capes, canes, and porkpie hats were his later signature dressing style. He held lofty opinions of himself and his creative gifts and proclaimed them often, and publicly. He was conservative and religious by upbringing, but his actions were ingrained by the family motto “Truth against the World”. He used this to justify his nonconforming professional and life choices.

Our baking workshop group was geographically represented from the east coast to the west, the south, and the mountains of Colorado. There was a mother/daughter duo, a married couple, and the rest of us came as single bakers–four men and six women. Several people were already experienced bread bakers. After the welcoming introductory afternoon including a champagne reception in Taliesin’s main living room, touring the house’s inner sanctums, and dinner in town, we were bonded as a group.

I was probably the least interested in taking sourdough bread making into my own kitchen, challenged by an altitude of 8300 feet. I might have been the most versed in Frank Lloyd Wright history, trivia, and lore. To each their own interests. But baking my own “boule” of country loaf was what got me there and set the daily schedule of morning and afternoon. We started right after breakfast on Day 2.

Bazile Booth is a professional baker with a successful storefront and business in downtown Spring Green. She is also a great teacher with a laid-back approach toward getting 10 pairs of hands to wind up with a successful loaf of bread. We measured and weighed ingredients, then waited to let the natural fermentation process of water and flour and sourdough starter begin their magic.

We hovered over our bowls, cheered each other’s success while bubbles formed as the yeast grew active. We stretched and turned the dough to aerate it. It took all day.

We didn’t bake the bread until Day 3. Instead, the dough “rested” in cloth lined baskets in the refrigerator until it was successfully turned into a beautiful brown loaf the next morning. After the final lunch we claimed our loaves to take home as if they were newborn babies.

Frank Lloyd Wright evolved into a successful and sought after architectural designer who was artistically ahead of his time. Then, he fell deeply in love with the wife of a neighbor and client in Oak Park, Illinois at a time when marriages were not easily dissolved. When they could no longer deny their attraction and desire to be together, Frank and Mamah (pronounced May-ma) sat together with their spouses, Catherine Wright and Edwin Cheney, to explain the situation. Frank’s Victorian-era wife flatly refused to divorce him so Frank and Mamah left the country for a year, in 1909, where they both worked in Europe.

Mamah was intelligent, highly educated, lovely, and an early feminist before that was a trend. Fluent in several languages, she taught school while in Germany. Then she was hired to translate the writings of a Swedish feminist, Evelyn Keys, whose work she and Frank admired and followed. Some of it formed the basis of what they believed about living together in love, even without a legal contract. Frank was busy working on a portfolio book of his work for publication in Berlin. They were often apart, but it was a break from the excruciating gossip back home. Upon returning in 1910, Edwin Cheney divorced Mamah, but Catherine Wright steadfastly refused to sign papers. Instead, she encouraged media attention to humiliate and denigrate her husband who broke convention and remained in his relationship with Mamah.

In 1911, to escape relentless criticism fueled by the newspapers, Wright designed and built Taliesin in the ancestral countryside west of Madison on land his mother purchased.

Three years later, in August 1914, Lloyd Wright suffered a devastating loss of love and property when a mentally deranged employee killed seven people on the estate while Frank and one of his sons were working on an uncompleted project (Midway Gardens) in Chicago. It was more gruesome than anyone could imagine, especially for Wright when returning to the aftermath.

Julian Carlton, houseman at the time, served the lunch soup on a hot summer day to Mamah and her two children, seated on a screened-in porch. Then he broke her skull with a “shingling hatchet” before turning the weapon on young John and Martha. Workers, gardeners, and apprentices were dining in another area of the house. Julian again served the soup, bolted the door shut, spread gasoline outside the room until it ran underneath the door, then ignited it. Men who tried to escape were attacked with the hatchet. By the end of that horrific day, seven people were murdered by axing and/or burning to death. Two-thirds of Taliesin was in smoldering ashes.

Frank’s son, John Lloyd Wright, made this observation about his father. “Something in him died with her, a something lovable and gentle that I knew and loved…As I reflect now, I am convinced that the love that united them was deep, sincere and holy in spite of its illegality–I am convinced that the woman for whom he left home was of noble character.”

Wright, numbed by emotional and physical pain, his body broken out in boils, eventually realized that faith and hope were now lost to him. “Something strange had happened to me. Instead of feeling that she, whose life had joined mine there at Taliesin, was a spirit near, she was utterly gone. After the first anguish of loss, a kind of black despair seemed to paralyze my imagination in her direction and numbed my sensibilities. The blow was too severe.” As a form of consolation, he felt that only by immersing in the work of rebuilding Taliesin could he get relief. “In action, there is release from anguish of mind.”

Taliesin II rose from the ashes in a completely new rendition. And then again, in 1925, when faulty wiring caused another fire, Wright rebuilt it for the third time into the current version.

One hundred years after the second redesign and rebuilding of Taliesin I walked around the estate grounds as the light changed from late afternoon to dusk. I wanted to feel what Frank and Mamah lived together in this rich green farmland with the hills and a river running through it. I wondered why Wright was compelled to rebuild after not one, but two devastating fires. What was it about this rural setting on a verdant hillside with expansive views overlooking the Wisconsin River that inspired him to continue life there after immeasurable tragedy?

I worked my way around the landscape, sitting in various spots to photograph scenery and imagining the bevy of apprentice architects who laboriously built the stone walls, walkways, and gardens a long time ago. I thought about how and why it framed Frank and Mamah’s short life together there over three years. The reasons began in his childhood.

Frank’s love and loyalty to the land began as a boy when he labored on Uncle James Lloyd-Jones’ farm summer after summer. It was a grueling learning curve to a stronger body and a fierce work ethic. He termed the phrase, “tired on tired” to describe the relentless fatigue and suffering endured from being wakened at 4:00 AM until falling into bed at night. But that steady seasonal diet of hard physical farm work set a high standard for the rest of his working life, seven decades, until his death at 92.

Wisconsin farmland, orchards, green wooded hills, a flowing river and nature were Wright’s roots. He built and rebuilt Taliesin here, pushing through times of great loss and suffering through the work. He returned when he needed to go home and restore his spirit. The landscape and the memories were the foundation of his physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health.

I first encountered the term “spiritual geography” in a book by Kathleen Nolan called Dakota: A Spiritual Geography. It’s the story of how she returned to the territory of her upbringing in South Dakota when her grandparents died. She and her husband traveled from New York City to settle the estate and ended up staying there for 25 years. The premise is that where you are from forms a part of your spiritual expression and never leaves you. Spiritual geography is the beginning of how we see and inhabit the world and how it inhabits us. It is where and how we learn the lessons to slow down, savor peace, solitude, and open spaces (where they are available). We take the lessons from our earliest remembered spiritual geographies and live the concept wherever we go.

I understand it two ways. My early childhood years were spent in a small suburb of St. Louis, Missouri with regular visits to the farm where my grandmother lived 30 miles away. It gave me comforts, freedoms and connection to both city and country living. Later, moving to Colorado in married life, a small town in the mountains bordering a national park became my grown-up spiritual geography. As we navigated life with two children in five countries around the world, always creating a home wherever we lived, I knew where the permanent “home” was waiting. It was where we refreshed our spirits every summer during the overseas years–in a mountainous landscape larger than we were that diminished the small details of life.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s return to the rural hills of his youth regenerated and nurtured his soul over a lifetime. Later, after his marriage to Olgivanna, he created a second spiritual geography near Scottsdale, Arizona. The desert environment and beauty of the southwest resonated with them both. Taliesin West was built, using the landscape as a guide, for their winter home. Wisconsin and Arizona remained an important summer/winter hiatus for the rest of their lives. They found spiritual renewal in both places.

The weekend at Taliesin reinforced my belief that how we create and inhabit our homes and personal spaces is another form of spiritual geography. Not landscape based, but living based. If we are fortunate, we can have both. Our home spaces (and how we live in them) provide emotional nurturing, too. Developing “inside geography” takes thought and effort. It requires letting go of anyone and everyone else’s notions of what is nourishing and meaningful in your life. It requires spending real time thinking, imagining, and playing with both practical and aesthetic beauty. Then, as Frank Lloyd Wright, you go about the work. You take up the action by collecting, arranging and rearranging. It’s a continual process. It can evolve over years. But, in time, you wake up every day in your version of spiritual geography.

WHY I LOVE WISCONSIN

By Frank Lloyd Wright

(Excerpts from an essay posted inside the Taliesin house)

I love Wisconsin because my staunch old Welsh grandfather with my gentle grandmother and their 10 children settled here nearby. I see the site of their homestead and those of their offspring as I write. Offspring myself, my home and workshop are planted on the ground grandfather and sons broke before the Indians had entirely gone away.

This Wisconsin valley with the spring-water stream winding down as its center line has been looked forward to or back upon by me and mine from all over the world, as home.

And I come back from the distant, strange, and beautiful places that I used to read about when I was a boy and wonder about; yes, every time I come back here it is with the feeling there is nothing anywhere better than this is.

More dramatic elsewhere, perhaps more strange, more thrilling, more grand, too, but nothing that picks you up in its arms and so gently, almost lovingly, cradles you as do these southwestern Wisconsin hills…

…Wisconsin soil has put sap into my veins. Why, I should love her as I loved my mother, my old grandmother, and as I love my work.

Resources (and quotes) used in this story are from:

Frank Lloyd Wright, A Life by Ada Louise Huxtable, 2004, Penguin Books (a short and very readable biography of the man, accounting for both flaws and genius)

Death in a Prairie House by William Drennan, 2007, University of Wisconsin Press (a detailed background, history, and accounting of the murders at Taliesin in 1914)

Dakota: A Spiritual Geography by Kathleen Norris, 1993, Houghton Mifflin Co. (coming home to find yourself)

A Brave and Lovely Woman, Mamah Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright by Mark Borthwick, 2023, University of Wisconsin Press (distant relative of Mamah Borthwick writes a detailed portrait of her life, before and with FLW)

More about creating spiritual geography at home: The Poetry of Space

Childhood spiritual geography in rural Missouri: The Coleman House, Villa Ridge, Missouri

Adult spiritual geography in the Colorado mountains: Bugling Elk and Sacred Spaces

End Note:

Over the past year the true bread bakers in our Taliesin workshop have shared multiple emails with suggestions, successes and failures, tidbits learned in their home kitchens, encouragements, book recommendations and photos. It remains a group where the journey continues in practice and spirit. I came to Taliesin because of an artisanal bread workshop and to gather information to write a story. I dedicate this to all the bakers from that weekend, and to Elizabeth (Bazile) Booth, teacher extraordinaire, owner of Sky Blue Pink Bakery in Spring Green, and Caroline Hamblen, our guide and Director of Programs at Taliesin Preservation.

Discover more from A Taste of Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This was such fun to read, while also being challenging. The fun was so easy as the photos and the writing invited me, and embraced me. The challenging is always the underlying issues – where SHOULD we be? And must there be a must?

Thank you for the provocation. Sending love from NM.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Provocations are good even over something as banal as an oyster. I must say, though, that it is always the people I’m with that make the experience one to remember. You and Sally in Paris for two years? Oh yes!

LikeLike

Wonderful writing, as always, Wendy. And stunning photographs!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely loved reading this article and learning the whole story of Frank Lloyd Wright’s life, his work, his struggles and his perseverance. His attachment to the land and nature are inspiring! Today I am going to make a loaf of bread!!! I love you Wendy!! You’re the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jane, love this comment. Thank you! You’re the best too.

LikeLike

Wendy, from your carefully chosen words to the images you’ve captured, I hear the story in your voice and see the images through your eyes, and I am transported.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gerri-Ann, strong compliments from my early tech mentor! It’s always a pleasure to see who pops up reading my musings. This is a special one to me. Thank you for weighing in.

LikeLike